I have lived in Canada for over 16 years so I was surprised when, a few months ago, a conference-friend whom I had not seen for many years contacted me to ask whereabouts in Malaysia I lived. I believe that they were misremembering a connection from a conversation long ago in which I’d mentioned a recent visit (it was in fact a day-trip from Singapore) and combining that with the accurate recollection that I no longer lived in the UK.

I have lived in Canada for over 16 years so I was surprised when, a few months ago, a conference-friend whom I had not seen for many years contacted me to ask whereabouts in Malaysia I lived. I believe that they were misremembering a connection from a conversation long ago in which I’d mentioned a recent visit (it was in fact a day-trip from Singapore) and combining that with the accurate recollection that I no longer lived in the UK.

Not long after, I was on a panel discussing the impact of ChatGPT during which I prompted ChatGPT to introduce me. Here was its first attempt in response to the prompt “tell me about Jon Dron”. I’ve highlighted things that are true in green, and things that are false in red (emphasized for those unable to see the colours):

Jon Dron is a Canadian educator, researcher, and writer. He is known for his work in the field of e-learning and collaborative technologies. Dron has a PhD in Educational Technology from the University of Calgary, and has held academic positions at several universities in Canada, including Athabasca University, where he is currently a professor.

Dron has written extensively on topics such as online learning, social media, and the use of technology in education. He is the author of several books, including “Teaching Crowds: Learning and Social Media” and “E-Learning Theory and Practice.”

In addition to his academic work, Dron is also a musician and has released several albums of ambient and experimental music.

I’d say that there is not much difference between the human and machine recollections. I would almost certainly make at least as many mistakes if I were to asked to confidently describe a person I don’t know particularly well. In fact, I might make similar mistakes (not, please note, hallucinations) about quite close friends. Most of us don’t have eidetic memories: we reinvent recollections as much as we recall them. While there are surely many profound differences between how humans and large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT process information, this is at least circumstantial evidence that some of the basic principles underlying artificial neural networks and biological neural networks are probably pretty similar. True, AIs do not know when they are making things up (or telling the truth, for that matter) but, in fairness, much of the time, neither do we. With a lot of intentional training we may be able to remember lines in a play or how to do long division but, usually, our recollections are like blurry JPEGs rather than RAW images.

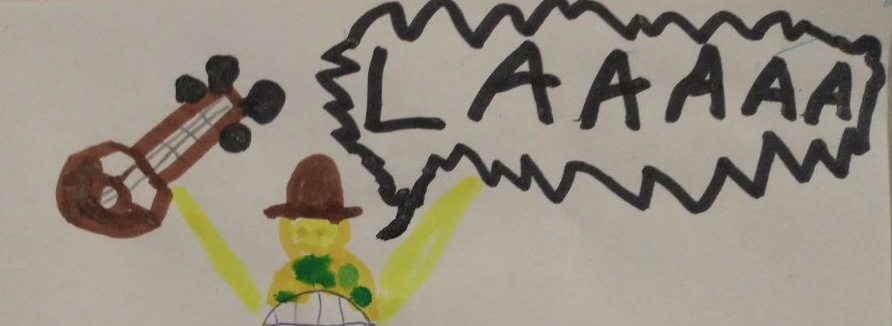

Even for things we have intentionally learned to do or recall well, it is unusual for that training to stick without continual reinforcement, and mistakes are easily made. A few days ago I performed a set of around 30 songs (neither ambient nor experimental), most of which I had known for decades, all of which I had carefully practiced in the days leading up to the event to be sure I could play them as I intended. Here is a picture of me singing at that gig, drawn by my 6-year-old grandchild who was in attendance:

Despite my precautions and ample experience, in perhaps a majority of songs, I variously forgot words, chords, notes, and, in a couple of cases, whole verses. Combined with errors of execution (my fingers are not robotic, my voice gets husky) there was, I think, only one song in the whole set that came out more or less exactly as I intended. I have made such mistakes in almost every gig I have ever played. In fact, in well over 40 years as a performer, I have never played the same song in exactly the same way twice, though I have played some of them well over 10,000 times. Most of the variations are a feature, not a bug: they are where the expression lies. A performance is a conversation between performer, instruments, setting, and audience, not a mechanical copy of a perfect original. Nonetheless, my goal is usually to at least play the right notes and sing the right words, and I frequently fail to do that. Significantly, I generally know when I have done it wrong (typically a little before in a dread realization that just makes things worse) and adapt fairly seamlessly on the fly so, on the whole, you probably wouldn’t even notice it has happened, but I play much like ChatGPT responds to prompts: I fill in the things I don’t know with something more or less plausible. These creative adaptations are no more hallucinations than the false outputs of LLMs.

The fact that perfect recall is so difficult to achieve is why we need physical prostheses, to write things down, to look things up, or to automate them. Given LLMs’ weaknesses in accurate recall, it is slightly ironic that we often rely on computers for that. It is, though, considerably more difficult for an LLM to do this because they have no big pictures, no purposes, no plans, not even broad intentions. They don’t know whether what they are churning out is right or wrong, so they don’t know to correct it. In fact, they don’t even know what they are saying, period. There’s no reflection, no metacognition, no layers of introspection, no sense of self, nothing to connect concepts together, no reason for them to correct errors that they cannot perceive.

Things that make us smart

How difficult can it be to fix this? I think we will soon be seeing a lot more solutions to this problem because if we can look stuff up then so can machines, and more reliable information from other systems can be used to feed the input or improve the output of the LLM (Bing, for instance, has been doing so for a while now, to an extent). A much more intriguing possibility is that an LLM itself or subsystem of it might not only look things up but also write and/or sequester code it needs to do things it is currently incapable of doing, extending its own capacity by assembling and remixing higher-level cognitive structures. Add a bit of layering then throw in an evolutionary algorithm to kill of the less viable or effective, and you’ve got a machine that can almost intentionally learn, and know when it has made a mistake.

Such abilities are a critical part of what makes humans smart, too. When discussing neural networks it is a bit too easy to focus on the underlying neural correlates of learning without paying much (if any) heed to the complex emergent structures that result from them – the “stuff” of thought – but those structures are the main things that make it work for humans. Like the training sets for large language models, the intelligence of humans is largely built from the knowledge gained from other humans through language, pedagogies, writing, drawing, music, computers, and other mediating technologies. Like an LLM, the cognitive technologies that result from this (including songs) are parts that we assemble and remix to in order to analyze, synthesize, and create. Unlike most if not all existing LLMs, though, the ways we assemble them – the methods of analysis, the rules of logic, the pedagogies, the algorithms, the principles, and so on (that we have also learned from others) – are cognitive prostheses that play an active role in the assembly, allowing us to build, invent, and use further cognitive prostheses and so to recursively extend our capabilities far beyond the training set, as well as to diagnose our own shortfalls.

Like an LLM, our intelligence is also fundamentally collective, not just in what happens inside brains, but because our minds are extended, through tools, gadgets, rules, language, writing, structures, and systems that we enlist from the world as part of (not only adjuncts to) our thinking processes. Through technologies, from language to screwdrivers, we literally share our minds with others. For those of us who use them, LLMs are now as much parts of us as our own creative outputs are parts of them.

All of this means that human minds are part-technology (largely but not wholly instantiated in biological neural nets) and so our cognition is about as artificial as that of AIs. We could barely even think without cognitive prostheses like language, symbols, logic, and all the countless ways of doing and using technologies that we have devised, from guitars to cars. Education, in part, is a process of building and enlisting those cognitive prostheses in learners’ minds, and of enabling learners to build and enlist their own, in a massively complex, recursive, iterative, and distributed process, rich in feedback loops and self-organizing subsystems.

Choosing what we give up to the machine

There are many good ways to use LLMs in the learning process, as part of what students do. Just as it would be absurd to deny students the use of pens, books, computers, the Internet, and so on, it is absurd to deny them the use of AIs, including in summative assessments. These are now part of our cognitive apparatus, so we should learn how to participate in them wisely. But I think we need to be extremely cautious in choosing what we delegate to them, above all when using them to replace or augment some or all of the teaching role.

What makes AIs different from technologies of the past is that they perform a broadly similar process of cognitive assembly as we do ourselves, allowing us to offload much more of our cognition to an embodied collective intelligence created from the combined output of countless millions of people. Only months after the launch of ChatGPT, this is already profoundly changing how we learn and how we teach. It is disturbing and disruptive in an educational context for a number of reasons, such as that:

- it may make it unnecessary for us to learn its skills ourselves, and so important aspects of our own cognition, not just things we don’t need (but which are they?), may atrophy;

- if it teaches, it may embed biases from its training set and design (whose?) that we will inherit;

- it may be a bland amalgam of what others have written, lacking originality or human quirks, and that is what we, too, will learn to do;

- if we use it to teach, it may lead students towards an average or norm, not a peak;

- it renders traditional forms of credentialling learning largely useless.

We need solutions to these problems or, at least, to understand how we will successfully adapt to the changes they bring, or whether we even want to do so. Right now, an LLM is not a mind at all, but it can be a functioning part of one, much as an artificial limb is a functioning part of a body or a cyborg prosthesis extends what a body can do. Whether we feel any particular limb that it (partly) replicates needs replacing, which system we should replace it with, and whether it is a a good idea in the first place are among the biggest questions we have to answer. But I think there’s an even bigger problem we need to solve: the nature of education itself.

AI teachers

There are no value-free technologies, at least insofar as they are enacted and brought into being through our participation in them, and the technologies that contribute to our cognition, such as teaching, are the most value-laden of all, communicating not just the knowledge and skills they purport to provide but also the ways of thinking and being that they embody. It is not just what they teach or how effectively they do so, but how they teach, and how we learn to think and behave as a result, that matters.

While AI teachers might well make it easier to learn to do and remember stuff, building hard cognitive technologies (technique, if you prefer) is not the only thing that education does. Through education, we learn values, ways of connecting, ways of thinking, and ways of being with others in the world. In the past this has come for free when we learn the other stuff, because real human teachers (including textbook authors, other students, etc) can’t help but model and transmit the tacit knowledge, values, and attitudes that go along with what they teach. This is largely why in-person lectures work. They are hopeless for learning the stuff being taught but the fact that students physically attend them makes them great for sharing attitudes, enthusiasm, bringing people together, letting us see how other people think through problems, how they react to ideas, etc. It is also why recordings of online lectures are much less successful because they don’t, albeit that the benefits of being able to repeat and rewind somewhat compensate for the losses.

What happens, though, when we all learn how to be human from something that is not (quite) human? The tacit curriculum – the stuff through which we learn ways of being, not just ways of doing – for me looms largest among the problems we have to solve if we are to embed AIs in our educational systems, as indeed we must. Do we want our children to learn to be human from machines that haven’t quite figured out what that means and almost certainly never will?

Many AI-Ed acolytes tell the comforting story that we are just offloading some of our teaching to the machine, making teaching more personal, more responsive, cheaper, and more accessible to more people, freeing human teachers to do more of the human stuff. I get that: there is much to be said for making the acquisition of hard skills and knowledge easier, cheaper, and more efficient. However, it is local thinking writ large. It solves the problems that we have to solve today that are caused by how we have chosen to teach, with all the centuries-long path dependencies and counter technologies that entails, replacing technologies without wondering why they exist in the first place.

Perhaps the biggest of the problems that the entangled technologies of education systems cause are the devastating effects of tightly coupled credentials (and their cousins, grades) on intrinsic motivation. Much of the process of good teaching is one of reigniting that intrinsic motivation or, at least, supporting the development of internally regulated extrinsic motivation, and much of the process of bad teaching is about going with the flow and using threats and rewards to drive the process. As long as credentials remain the primary reason for learning, and as long as they remain based on proof of easily measured learning outcomes provided through end-products like assignments and inauthentic tests, then an AI that offers a faster, more efficient, and better tailored way of achieving them will crowd out the rest. Human teaching will be treated as a minor and largely irrelevant interruption or, at best, a feel-good ritual with motivational perks for those who can afford it. And, as we are already seeing, students coerced to meet deadlines and goals imposed on them will use AIs to take shortcuts. Why do it yourself when a machine can do it for you?

The future

As we start to build AIs more like us, with metacognitive traits, self-set purposes, and the capacity for independent learning, the problem is just going to get bigger. Whether they are better or worse (they will be both), AIs will not be the same as us, yet they will increasingly seem so, and increasingly play human roles in the system. If the purpose of education is seen as nothing but short-term achievement of explicit learning outcomes and getting the credentials arising from that, then it would be better to let the machines achieve them so that we can get on with our lives. But of course that is not the purpose. Education is for preparing people to live better lives in better societies. It is why the picture of me singing above delights me more than anything ever created by an AI. It is why education is and must remain a fundamentally human process. Almost any human activity can be replaced by an AI, including teaching, but education is fundamental to how we become who we are. That’s not the kind of thing that I think we want to replace.

Our minds are already changing as they extend into the collective intelligence of LLMs – they must – and we are only at the very beginning of this story. Most of the changes that are about to occur will be mundane, complex, and the process will be punctuated but gradual, so we won’t really notice what has been happening until it has happened, by which time it may be too late. It is probably not an exaggeration to say that, unless environmental or other disasters don’t bring it all to a halt, this is a pivotal moment in our history.

It is much easier to think locally, to think about what AIs can do to support or extend what we do now, than it is to imagine how everything will change as a result of everyone doing that at scale. It requires us to think in systems, which is not something most of us are educated or prepared to do. But we must do that, now, while we still can. We should not leave it to AIs to do it for us.

There’s much more on many of the underpinning ideas mentioned in this post, including references and arguments supporting them, in my freely downloadable or cheap-to-purchase latest book (of three, as it happens), How Education Works.