Tony Bates extensively referenced this report from the Royal Bank of Canada on Canadian employer demands for skills over the next few years, in his characteristically perceptive keynote at CNIE 2019 last week (it’s also referred to in his most recent blog post). It’s an interesting read. Central to its many findings and recommendations are that the Canadian education system is inadequately designed to cope with these demands and that it needs to change. The report played a big role in Tony’s talk, though his thoughts on appropriate responses to that problem were independently valid in and of themselves, and not all were in perfect alignment with the report.

The 43-page manifesto (including several pages of not very informative graphics) combines some research findings, with copious examples to illustrate its discoveries, and with various calls to action based on them. I guess not surprisingly for a document intended to ignite, it is often rather hard to tell in any detail how the research itself was conducted. The methodology section is mainly on page 33 but it doesn’t give much more than a broad outline of how the main clustering was performed, and the general approach to discovering information. It seems that a lot of work went into it, but it is hard to tell how that work was conducted.

A novel (-ish) finding: skillset clusters

Perhaps the most distinctive and interesting research discovery in the report is a predictive/descriptive model of skillsets needed in the workplace. By correlating occupations from the federal NOC (National Occupational Classification) with a US Labor Department dataset (O*NET) the researchers abstracted and identified six distinct clusters of skillsets, the possessors of which they characterize as:

- solvers (engineers, architects, big data analysts, etc)

- providers (vets, musicians, bloggers, etc)

- facilitators (graphic designers, admin assistants, Uber drivers, etc)

- technicians (electricians, carpenters, drone assemblers, etc)

- crafters (fishermen, bakers, couriers, etc)

- doers (greenhouse workers, cleaners, machine-learning trainers, etc)

From this, they make the interesting, if mainly anecdotally supported, assertion that there are clusters of occupations across which these skills can be more easily transferred. For instance, they reckon, a dental assistant is not too far removed from a graphic designer because both are high on the facilitator spectrum (emotional intelligence needed). They do make the disclaimer that, of course, other skills are needed and someone with little visual appreciation might not be a great graphic designer despite being a skilled facilitator. They also note that, with training, education, apprenticeship models, etc, it is perfectly possible to move from one cluster to another, and that many jobs require two or more anyway (mine certainly needs high levels of all six). They also note that social skills are critical, and are equally important in all occupations. So, even if their central supposition is true, it might not be very significant.

There is a somewhat intuitive appeal to this, though I see enormous overlap between all of the clusters and find some of the exemplars and descriptions of the clusters weirdly misplaced: in what sense is a carpenter not a crafter, or a graphic designer not a provider, or an electrician not a solver, for instance? It treads perilously close to the borders of x-literacies – some variants of which come up with quite similar categories – or learning style theories, in its desperate efforts to slot the world into manageable niches regardless of whether there is any point to doing so. The worst of these is the ‘doers’ category, which seems to be a lightly veiled euphemism for ‘unskilled’ (which, as they rightly point out, relates to jobs that are mostly under a great deal of threat). ‘Doing’ is definitely ripe for transfer between jobs because mindless work in any occupation needs pretty much the same lack of skill. My sense is that, though it might be possible to see rough patterns in the data, the categories are mostly very fuzzy and blurred, and could easily be used to label people in very unhelpful ways. It’s interesting from a big picture perspective, but, when you’re applying it to individual human beings, this kind of labelling can be positively dangerous. It could easily lead to a species of the same general-to-specific thinking that caused the death of many airplane pilots prior to the 1950s, until the (obvious but far-reaching) discovery that there is no such thing as an average-sized pilot. You can classify people into all sorts of types, but it is wrong to make any further assumptions about them because you have done so. This is the fundamental mistake made by learning style theorists: you can certainly identify distinct learner types or preferences but that makes no difference whatsoever to how you should actually teach people.

Education as a feeder for the job market

Perhaps the most significant and maybe controversial findings, though, are those leading more directly to recommendations to the educational and training sector, with a very strong emphasis on preparedness for careers ahead. One big thing bothers me in all of this. I am 100% in favour of shifting the emphasis of educational institutions from knowledge acquisition to more fundamental and transferable capabilities: on that the researchers of this report hit the nail on the head. However, I don’t think that the education system should be thought of, primarily, as a feeder for industry or preparation for the workplace. Sure, it’s definitely one important role for education, but I don’t think it’s the dominant one, and it’s very dangerous indeed to make that its main focus to the exclusion of the rest. Education is about learning to be a human in the context of a society; it’s about learning to be part of that culture and at least some of its subcultures (and, ideally, about understanding different cultures). It’s a huge binding force, it’s what makes us smart, individually and collectively, and it is by no means limited to things we learn in institutions or organizations. Given their huge role in shaping how we understand the world, at the very least media (including social media) should, I think, be included whenever we talk of education. In fact, as Tony noted, the shift away from institutional education is rapid and on a vast scale, bringing many huge benefits, as well as great risks. Outside the institutions designed for the purpose, education is often haphazard, highly prone to abuse, susceptible to mob behaviours, and often deeply harmful (Trump, Brexit, etc being only the most visible tips of a deep malaise). We need better ways of dealing with that, which is an issue that has informed much of my research. But education (whether institutional or otherwise) is for life, not for work.

I believe that education is (and should be) at least partly concerned with passing on what we know, who we have been, who we are, how we behave, what we value, what we share, how we differ, what drives us, how we matter to one another. That is how it becomes a force for societal continuity and cohesion, which is perhaps its most important role (though formal education’s incidental value to the economy, especially through schools, as a means to enable parents to work cannot be overlooked). This doesn’t have to exclude preparation for work: in fact, it cannot. It is also about preparing people to live in a culture (or cultures), and to continue to learn and develop productively throughout their lives, evolving and enhancing that culture, which cannot be divorced from the tools and technologies (including rituals, norms, rules, methods, artefacts, roles, behaviours, etc) of which the cultures largely consist, including work. Of course we need to be aware of, and incorporate into our teaching, some of the skills and knowledge needed to perform jobs, because that’s part of what makes us who we are. Equally, we need to be pushing the boundaries of knowledge ever outwards to create new tools and technologies (including those of the arts, the humanities, the crafts, literature, and so on, as well as of sciences and devices) because that’s how we evolve. Some – only some – of that will have value to the economy. And we want to nurture creativity, empathy, social skills, communication skills, problem-solving skills, self-management skills, and all those many other things that make our culture what it is and that allow us to operate productively within it, that also happen to be useful workplace skills. But human beings are also much more than their jobs. We need to know how we are governed, the tools needed to manage our lives, the structures of society. We need to understand the complexities of ethical decisions. We need to understand systems, in all their richness. We need to nurture our love of arts, sports, entertainment, family life, the outdoors, the natural and built environment, fine (and not fine) dining, being with friends, talking, thinking, creating stuff, appreciating stuff, and so on. We need to develop taste (of which Hume eloquently wrote hundreds of years ago). We need to learn to live together. We need to learn to be better people. Such things are (I think) more who we are, and more what our educational systems should focus on, than our productive roles in an economy. The things we value most are, for the most part, seldom our economic contributions to the wealth of our nation, and the wealth of a nation should never be measured in economic terms. Even those few that love money the most usually love the power it brings even more, and that’s not the same thing as economic prosperity for society. In fact, it is often the very opposite.

I’m not saying economic prosperity is unimportant, by any means: it’s often a prerequisite for much of the rest, and sometimes (though far from consistently) a proxy marker for them. And I’m not saying that there is no innate value in the process of achieving economic prosperity: many jobs are critical to sustaining that quality of life that I reckon matters most, and many jobs actually involve doing the very things we love most. All of this is really important, and educational systems should cater for it. It’s just that future employment should not be thought of as the main purpose driving education systems.

Unfortunately, much of our teaching actually is heavily influenced by the demands of students to be employable, heavily reinforced on all sides by employers, families, and governments, and that tends to lead to a focus on topics, technical skillsets, and subject knowledge, not so much to the exclusion of all the rest, but as the primary framing for it. For instance, HT to Stu Berry and Terry Anderson for drawing my attention to the mandates set by the BC government for its post secondary institutions, that are a litany of shame, horribly focused on driving economic prosperity and feeding industry, to the exclusion of almost anything else (including learning and teaching, or research for the sake of it, or things that enrich us as human beings rather than cogs in an economic machine). This report seems to take the primary role of education as a driver of economic prosperity as just such a given. I guess, being produced by a bank, that’s not too surprising, but it’s worth viewing it with that bias in mind.

And now the good news

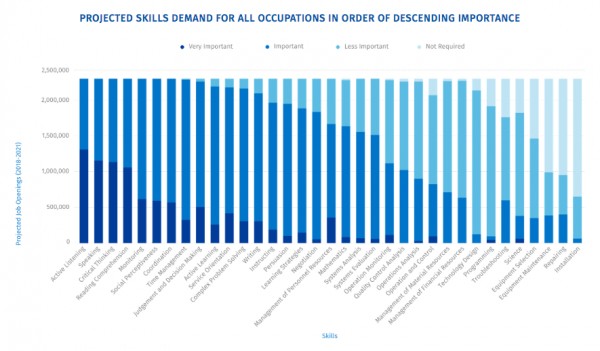

What is heartwarming about this report, though, is that employers seem to want (or think they will want) more or less exactly those things that also enrich our society and our personal lives. Look at this fascinating breakdown of the skills employers think they will need in the future (Tony used this in his slides):

There’s a potential bias due to the research methodology, that I suspect encouraged participants to focus on more general skills, but it’s really interesting to see what comes in the first half and what dwindles into unimportance at the end.

Topping the list are active listening, speaking, critical thinking, comprehension, monitoring, social perceptiveness, coordination, time management, judgement and decision-making, active learning, service orientation, complex problem solving, writing, instructing, persuasion, learning strategies, and so on. These mostly quite abstract skills (in some cases propensities, albeit propensities that can be cultivated) can only emerge within a context, and it is not only possible but necessary to cultivate them in almost any educational intervention in any subject area, so it is not as though they are being ignored in our educational systems. More on that soon. What’s interesting to me is that they are the human things, the things that give us value regardless of economic value. I find it slightly disconcerting that ethical or aesthetic sensibilities didn’t make the list and there’s a surprising lack of mention of physical and mental health but, on the whole, these are life skills more than just work skills.

Conventional education can and often does cultivate these skills. I am pleased to brag that, as a largely unintentional side-effect of what I think teaching in my fields should be about, these are all things I aim to cultivate in my own teaching, often to the virtual exclusion of almost everything else. Sometimes I have worried (a little) that I don’t have very high technical expectations of my students. For instance, my advanced graduate level course in information management provides technical skills in database design and analysis that are, for the most part, not far above high-school level (albeit that many students go far beyond that); my graduate level social computing course demands no programming skills at all (technically, they are optional); my undergraduate introduction to web programming course sometimes leads to limited programming skills that would fail to get them a passing grade in a basic computer science course (though they typically pass mine). However (and it’s a huge HOWEVER) they have a far greater chance to acquire far more of those skills that I believe matter, and (gratifyingly) employers seem to want, than those who focus only on mastery of the tools and techniques. My web programming students produce sites that people might actually want to visit, and they develop a vast range of reflective, critical thinking, complex problem-solving, active learning, judgment, persuasion, social perceptiveness and other skills that are at the top of the list. My information management students get all that, and a deep understanding of the complex, social, situated nature of the information management role, with some notable systems analysis skills (not so much the formal tools, but the ways of understanding and thinking in systems). My social computing students get all that, and come away with deep insights into how the systems and environments we build affect our interactions with one another, and they can be fluent, effective users and managers of such things. All of the successful ones develop social and communication skills, appropriate to the field. Above all, my target is to help students to love learning about the subjects of my courses enough to continue to learn more. For me, a mark of successful teaching is not so much that students have acquired a set of skills and knowledge in a domain but that they can, and actually want to, continue to do so, and that they have learned to think in the right ways to successfully accomplish that. If they have those skills, then it is not that difficult to figure out specific technical skillsets as and when needed. Conveniently, and not because I planned it that way, that happens to be what employers want too.

Employers don’t (much) want science or programming skills: so what?

Even more interesting, perhaps, than the skills employers do want are the skills they do not want, from Operation Monitoring onwards in the list, that are often the primary focus of many of our courses. Ignoring the real nuts and bolts stuff at the very bottom like installation, repairing, maintenance, selection (more on that in a minute), it is fascinating that skills in science, programming, and technology design are hardly wanted at all by most companies, but are massively over-represented in our teaching. The writers of the report do offer the proviso that it is not impossible that new domains will emerge that demand exactly these skills but, right now and for the foreseeable future, that’s not what matters much to most organizations. This doesn’t surprise me at all. It has long been clear that the demand for people that create the foundations is, of course, going to be vastly much smaller than the demand for people that build upon them, let alone the vastly greater numbers that make use of what has been built upon them. It’s not that those skills are useless – that’s a million miles from the truth – but that there is a very limited job market for them. Again, I need to emphasize that educators should not be driven by job markets: there is great value in knowing this kind of thing regardless of our ability to apply it directly in our jobs. On the other hand, nor should we be driven by a determination to teach all there is to know about foundations, when what interests people (and employers, as it happens) is what can be done with them. And, in fact, even those building such foundations desperately need to know that too, or the foundations will be elegant but useless. Importantly, those ‘foundational’ skills are actually often anything but, because the emergent structures that arise from them obey utterly different rules to the pieces of which they are made. Knowing how a cell works tells you nothing whatsoever about function of a heart, let alone how you should behave towards others, because different laws and principles apply at different levels of organization. A sociologist, say, really doesn’t need to know much about brain science, even though our brains probably contribute a lot to our social systems, because it’s the wrong foundation, at the wrong level of detail. Similarly, there is not a lot of value in knowing how CPUs work if your job is to build a website, or a database system supporting organizational processes (it’s not useless, but it’s not very useful so, given limited resources, it makes little sense to focus on it). For almost all occupations (paid or otherwise) that make use of science and technology, it matters vastly much more to understand the context of use, at the level of detail that matters, than it does to understand the underlying substructures. This is even true of scientists and technologists themselves: for most scientists, social and business skills will have a far greater effect on their success than fundamental scientific knowledge. But, if students are interested in the underlying principles and technologies on which their systems are based, then of course they should have freedom and support to learn more about them. It’s really interesting stuff, irrespective of market demand. It enriches us. Equally, they should be supported in discovering gothic literature, social psychology, the philosophy of art, the principles of graphic design, wine making, and anything else that matters to them. Education is about learning to be, not just learning to do. Nothing of what we learn is wasted or irrelevant. It all contributes to making us creative, engaged, mutually supportive human beings.

With that in mind, I do wonder a bit about some of the skills at the bottom of the list. It seems to me that all of the bottom four demand – and presuppose – just about all of those in the top 12. At least, they do if they are done well. Similarly for a few others trailing the pack. It is odd that operation monitoring is not much desired, though monitoring is. It is strange that troubleshooting is low in the ranks, but problem-solving is high. You cannot troubleshoot without solving problems. It’s fundamental. I guess it speaks to the idea of transferability and the loss of specificity in roles. My guess is that, in answering the questions of the researchers, employers were hedging their bets a bit and not assuming that specific existing job roles will be needed. But conventional teachers could, with some justification, observe that their students are already acquiring the higher-level, more important skills, through doing the low-level stuff that employers don’t want as much. Though I have no sympathy at all with our collective desire to impose this on our students, I would certainly defend our teaching of things that employers don’t want, at least partly because (in the process) we are actually teaching far more. I would equally defend even the teaching of Latin or ancient Greek (as long as these are chosen by students, never when they are mandated) because the bulk of what students learn is never the skill we claim to be teaching. It’s much like what the late, wonderful, and much lamented Randy Pausch called a head fake – to be teaching one thing of secondary importance while primarily teaching another deeper lesson – except that rather too many teachers tend to be as deceived as their students as to the real purpose and outcomes of their teaching.

Automation and outsourcing

As the report also suggests, it may also be that those skills lower in the ranking tend to be things that can often be outsourced, including (sooner or later) to machines. It’s not so much that the jobs will not be needed, but that they can be either automated or concentrated in an external service provider, reducing the overall job market for them. Yes, this is true. However, again, the methodology may have played a large role in coming to this conclusion. There is a tendency of which we are all somewhat guilty to look at current patterns of change (in this case the trend towards automation and outsourcing) and to assume that they will persist into the future. I’m not so sure.

Outsourcing

Take the stampede to move to the cloud, for instance, which is a clear underlying assumption in at least the undervaluing of programming. We’ve had phases of outsourcing several times before over the past 50 or 60 years of computing history. Cloud outsourcing is only new to the extent that the infrastructure to support it is much cheaper and more well-established than it was in earlier cycles, and there are smarter technologies available, including many that benefit from scale (e.g. AI, big data). We are currently probably at or near peak Cloud, but it is just a trend even if it has yet to peak. It might last a little longer than the previous generations (which, of course, never actually went away – it’s just an issue of relative dominance) but it suffers from most of the problems that brought previous outsourcing hype cycles to an end. The loss of in-house knowledge, the dangers of proprietary lock-in, the surrender of control to another entity that has a different (and, inevitably, at some point conflicting) agenda, and so on, are all counter forces to hold outsourcing in check. History and common sense suggests that there will eventually be a reversal of the trend and, indeed, we are seeing it here and there already, with the emergence of private clouds, regional/vertical cloud layers, hybrid clouds, and so on. Big issues of privacy and security are already high on the agendas of many organizations, with an increasing number of governments starting to catch up with legislation that heavily restricts unfettered growth of (especially) US-based hosting, with all the very many very bad implications for privacy that entails. Increasingly, businesses are realizing that they have lost the organizational knowledge and intelligence to effectively control their own systems: decisions that used to be informed by experts are now made by middle-managers with insufficient detailed understanding of the complexities, who are easy prey for cloud companies willing to exploit their ignorance. Equally, they are liable to be flanked by those who can adapt faster and less uniformly, inasmuch as everyone gets the same tools in the Cloud so there is less to differentiate one user of it from the next. OK, I know that is a sweeping generalization – there are many ways to use cloud resources that do not rely on standard tools and services. We don’t have to buy in to the proprietary SaaS rubbish, and can simply move servers to containers and VMs while retaining control, but the cloud companies are persuasive and keen to lure us in, with offers of reduced costs, higher reliability, and increased, scalable performance that are very enticing to stressed, underfunded CIOs with immediate targets to meet. Right now, cloud providers are riding high and making ridiculously large profits on it, but the same was true of IBM (and its lesser competitors) in the 60s and 70s. They were brought down (though never fully replaced) by a paradigm change that was, for the most part, a direct reaction to the aforementioned problems, plus a few that are less troublesome nowadays, like performance and cost of leased lines. I strongly suspect something similar will happen again in a few years.

Automation and the end of all things we value

Automation – especially through the increased adoption of AI techniques – may be a different matter. It is hard to see that becoming less disruptive, albeit that the reality is and will be much more mundane than the hype, and there will be backlashes. However, I greatly fear that we have a lot of real stupidity yet to come in this. Take education, for instance. Many people whose opinions I otherwise respect are guilty of thinking that teachers can be, to a meaningful extent, replaced by chatbots. They are horribly misguided but, unfortunately, people are already doing it, and claiming success, not just in teaching but in fooling students that they are being taught by a real teacher. You can indeed help people to pass tests through the use of such tools. However, the only things that tests prove about learning is that you have learned to pass them. That’s not what education is for. As I’ve already suggested, education is really not much to do with the stuff we think we teach. It is about being and becoming human. If we learn to be human from what are, in fact, really very dumb machines with no understanding whatsoever of the words they speak, no caring for us, no awareness of the broader context of what they teach, no values to speak of at all, we will lower the bar for artificial intelligence because we will become so much dumber ourselves. It will be like being taught by an unusually tireless and creepily supportive (because why would you train a system to be otherwise?) person. We should not care for them, and that matters, because caring (both ways) is critical to the relationship that makes learning with others meaningful. But it will be even worse if and when we do start caring for them (remember the Tamagotchi?). When we start caring for soulless machines (I don’t mean ‘soul’ in a religious or transcendent sense), when it starts to matter to us that we are pleasing them, we will learn to look at one another in the same way and, in the process, lose our own souls. A machine, even one that fools us it is human, makes a very poor role model. Sure, let them handle helpdesk enquiries (and pass them on if they cannot help), let them supplement our real human interactions with useful hints and suggestions, let them support us in the tasks we have to perform, let them mark our tests to double-check we are being consistent: they are good at that kind of thing, and will get better. But please, please, please don’t let them replace teachers.

I am afraid of AI, not because I am bothered by the likelihood of an AGI (artificial general intelligence) superseding our dominant role on the planet: we have at least decades to think about that, and we can and will augment ourselves with dumb-but-sufficient AI to counteract any potential ill effects. The worst outcome of AI in the foreseeable future is that we devalue ourselves, that we mistake the semblance of humanity for humanity itself, that machines will become our role models. We may even think they are better than us, because they will have fewer human foibles and a tireless, on-demand, semblance of caring that we will mistake for being human (a bit like obsequious serving staff seeking tips in a restaurant, but creepier, less transparent, and infinitely patient). Real humans will disappoint us. Bots will be trained to be what their programmers perceive as the best of us, even though we don’t have more than the glimmerings of an idea of what ‘best’ actually means (philosophers continue to struggle with this after thousands of years, and few programmers have even studied philosophy at a basic level). That way the end of humanity lies: slowly, insidiously, barely noticeably at first. Not with a bang but with an Alicebot. Arthur C. Clark delightfully claimed that any teacher who could be replaced by a machine should be. I fear that we are not smart enough to realize that it is, in fact, very easy to successfully replace a teacher with a machine if you don’t understand the teacher’s true role in the educational machine, and you don’t make massive changes to it. As long as we think of education as the achievement of pre-specified outcomes that we measure using primitive tools like standardized tests, exams, and other inauthentic metrics, chatbots will quite easily supersede us, despite their inadequacies. It is way too easy to mistake the weirdly evolved educational system that we are part of for education itself: we already do so in countless ways. Learning management systems, for instance, are not designed for learning: they are designed to replicate mediaeval classrooms, with all the trimmings, yet they have been embraced by nearly all institutions because they fit the system. AI bots will fit even better. If we do intend to go down this path (and many are doing so already) then please let’s think of these bots as supplemental, first line support, and please let’s make it abundantly clear that they are limited, fixed-purpose mechanisms, not substitutes but supplements that can free us from trivial tasks to let us concentrate on being more human.

Co-ops and placements

The report makes a lot of recommendations, most of which make sense – e.g. lifelong support for learning from governments, focus on softer more flexible skills, focus on adaptability, etc. Notable among these is the suggestion, as one of its calls to action, that all PSE students should engage in some form of meaningful work-integrated learning placements during their studies. This is something that we have been talking about offering to our program students in computing for some time at Athabasca University, though the demand is low because a large majority of our students are already working while studying, and it is a logistical nightmare to do this across the whole of Canada and much of the rest of the globe. Though some AU programs embed it (nursing, for instance) I’m not sure we will ever get round to it in computing. I do very much agree that co-ops and placements are typically a good idea for (at least) vocationally-oriented students in conventional in-person institutions. I supervised a great many of these (for computing students) at my former university and observed the extremely positive effects it usually had, especially on those taking the more humanistic computing programs like information systems, applied computing, computer studies, and so on. When they came back from their sandwich year (UK terminology), students were nearly always far wiser, far more motivated, and far more capable of studying than the relatively few that skipped the opportunity. Sometimes they were radically transformed – I saw borderline-fail students turn into top performers more than once – but, apart from when things fell apart (not common, but not unheard of), it was nearly always worth far more than at least the previous couple of years of traditional teaching. It was expensive and disruptive to run, demanding a lot from all academic staff and especially from those who had to organize it all, but it was worth it.

But, just because it works in conventional institutions doesn’t mean that it’s a good idea. It’s a technological solution that works because conventional institutions don’t. Let’s step back a bit from this for a moment. Learning in an authentic context, when it is meaningful and relevant to clear and pressing needs, surrounded by all the complexities of real life (notwithstanding that education should buffer some of that, and make the steps less risky or painful), in a community or practice, is a really good idea. Apprenticeship models have thousands of years of successful implementation to prove their worth, and that’s essentially what co-ops or placements achieve, albeit only in a limited (typically 3-month to 1 year) timeframe. It’s even a good idea when the study area and working practices do not coincide, because it allows many more connections to be made in both aspects of life. But why not extend that to all (or almost all) of the process? To an extent, this is what we at Athabasca already do, although it tends to be more the default context than something we take intentional advantage of. Again, my courses are an exception – most of mine (and all to some extent) rely on students having a meaningful context of their own, and give opportunities to integrate work or other interests and study by default. In fact, one of the biggest problems I face in my teaching arises on those rare occasions when students don’t have sufficient aspects of work or leisure that engage them (e.g. prisoners or visiting students from other universities), or work in contexts that cannot be used (e.g. defence workers). I have seen it work for in-person contexts, too: the Teaching Company Scheme in the UK, that later became Knowledge Transfer Partnerships, has been hugely successful over several decades, marrying workplace learning with academic input, usually leading to a highly personalized MSc or MA while offering great benefits to lecturers, employers and students alike. They are fun, but resource-intensive, to supervise. Largely for this reason, in the past it might have been hard to make this scalable to lower than graduate levels of learning, but modern technologies – shared workspaces, blogs, portfolio management tools, rich realtime meeting tools, etc, and a more advanced understanding of ways to identify and record competencies – make it far more possible. It seems to me that what we want is not co-ops or placements, but a robust (and, ideally, publicly funded) approach to integrating academic and in-context learning. Already, a lot of my graduate students and a few undergraduates are funded by their employers, working on our courses at the same time as doing their existing jobs, which seems to benefit all concerned, so there’s clearly a demand. And it’s not just an option for vocational learning. Though (working in computing) much of my teaching does have a vocational grounding, if not a vocational focus, I have come across students elsewhere across the university who are doing far less obviously job-related studies with the support of their employers. In fact, it is often a much better idea for students to learn stuff that is not directly applicable to their workplace, because the boundary-crossing it entails better improves a vast range of the most important skills identified in the RBC report – creativity, communication, critical thinking, problem solving, judgement, listening, reading, and so on. Good employers see the value in that.

Conclusions

Though this is a long post, I have only cherry-picked a few of the many interesting issues that emerge from the report, but I think there are some general themes in my reactions to it that are consistent:

1: it’s not about money

Firstly, the notion that educational systems should be primarily thought of as feeders for industry is dangerous nonsense. Our educational systems are preparation for life (in society and its cultures), and work is only a part of that. Preparedness for work is better seen as a side-effect of education, not its purpose. And education is definitely not the best vehicle for driving economic prosperity. The teaching profession is almost entirely populated by extremely smart, capable, people who (especially in relation to their qualifications) are earning relatively little money. To cap it all, we often work longer hours, in poorer conditions than many of our similarly capable industry colleagues. Though a fair living wage is, of course, very important to us, and we get justly upset when offered unfair wages or worsening conditions, we don’t work for pay: we are paid for our work. Notwithstanding that a lack of money is a very bad thing indeed and should be avoided like the plague, we do so precisely because we think there are some things – common things – that are much more important than money (this may also partly account for a liberal bias in the profession, though it also helps that the average IQ of teachers is a bit above the norm). And, whether explicitly or otherwise, this is inevitably part of what we teach. Education is not primarily about learning a set of skills and facts: it’s about learning to be, and the examples that teachers set, the way they model roles, cannot help but come laden with their own values. Even if we scrupulously tried to avoid it, the fact of our existence serves as a prime example of people who put money relatively low on their list of priorities. If we have an influence (and I hope we do) we therefore encourage people to value things other than a large wage packet. So, if you are going to college or school in the hope of learning to make loads of money, you’re probably making the wrong choice. Find a rich person instead and learn from them.

2: it is about integrating education and the rest of our lives

Despite its relentless focus on improving the economy, I think this report is fundamentally right in most of the suggestions it makes about education, though it doesn’t go far enough. It is not so much that we should focus on job-related skills (whatever they might be) but that we should integrate education with and throughout our lives. The notion of taking someone out of their life context and inflicting a bunch of knowledge-acquisition tasks with inauthentic, teacher-led criteria for success, not to mention to subjugate them to teacher control over all that they do, is plain dumb. There may be odd occasions where retreating from and separating education from the world is worthwhile, but they are few and far between, and can be catered for on an individual needs basis.

Our educational processes evolved in a very different context, where the primary intent was to teach dogma to the many by the few, and where physical constraints (rarity of books/reading skills, limited availability of scholars, limits of physical spaces) made lecture forms in dedicated spaces appropriate solutions to those particular technical problems. Later, education evolved to focus more on creating a pliant and capable workforce to meet the needs of employers and the military, which happened to fit fairly well with the one-to-many top-down-control models devised to teach divinity etc. Though those days are mostly ended, we still retain strong echoes of these roles in much of our structure and processes – our pedagogies are still deeply rooted in the need to learn specific stuff, dictated and directed by others, in this weird, artificial context. Somehow along the way (in part due to higher education, at least, formerly being a scarce commodity) we turned into filters and gatekeepers for employment purposes. But, today, we are trying to solve different problems. Modern education has tended to tread a shifting path between supporting individual development and improving our societies: these should be mutually supportive roles though different educational systems tend to put more emphasis on one than the other. With that in mind, it no longer makes sense to routinely (in fact almost universally) take people out of their physical, social, or work context to learn stuff. There are times that it helps or may even be necessary: when we need access to expensive shared resources (that mediaeval problem again), for instance, or when we need to work with in-person communities (hard to teach acting unless you have an opportunity to act with other actors, for example), or when it might be notably dangerous to practice in the real world (though virtual simulations can help). But, on the whole, we can learn far better when we learn in a real world context, where we can put our learning directly into useful practice, where it has value to us and those around us. Community matters immensely – for learning, for motivation, for diversity of ideas, for belonging, for connection, etc – and one of the greatest values in traditional education is that it provides a ready-made social context. We should not throw the baby out with the bathwater and it is important to sustain such communities, online or in-person. But it does not have to be, and should not ever be, the only social context, and it does not need to be the main social context for learning. Pleasingly, in his own excellent keynote at CNIE, our president Neil Fassina made some very similar points. I think that Athabasca is well on course towards a much brighter future.

3: what we teach is not what you learn

Finally, the whole education system (especially in higher education) is one gigantic head fake. By and large, the subjects we teach are of relatively minor significance. We teach ways of thinking, we teach values, we teach a few facts and skills, but mainly we teach a way of being. For all that, what you actually learn is something else entirely, and it is different from what every one of your co-learners learns, because 1) you are your main and most important teacher and 2) you are surrounded by others (in person, in artefacts they create, online) who also teach you. We need to embrace that far more than we typically do. We need to acknowledge and celebrate the differences in every single learner, not teach stuff at them in the vain belief that what we have to tell you matters more than what you want to learn, or that somehow (contrary to all evidence) everyone comes in and leaves knowing the same stuff. We’ve got to stop rewarding and punishing compliance and non-compliance.

What you learn changes you. It makes you able to see things differently, do things differently, make new connections. Anything you learn. There is no such thing as useless learning. It is, though, certainly possible to learn harmful things – misconceptions, falsehoods, blind beliefs, and so on – so the most important skill is to distinguish those from the things that are helpful (not necessarily true – helpful). On the whole, I don’t like approaches to teaching that make you learn stuff faster (though they can be very useful when solving some kinds of problem) because it devalues the journey. I like approaches that help you learn better: deeper, more connected, more transformative. This doesn’t mean that the RBC report is wrong in criticizing our current educational systems, but it is wrong to believe that the answer is to stop (or reduce) teaching the stuff that employers don’t think they need. Learners should learn whatever they want or need to learn, whenever they need to do so, and educational institutions (collectively) should support that. But that also doesn’t mean teachers should teach what learners (or employers, or governments) think they should teach, because 1) we always teach more than that, whether we want to or not, and it all has value and 2) none of these entities are our customers. The heartbreaking thing is that some of the lessons most of us unintentionally teach – from mindless capitulation to authority, to the terrible approaches to learning nurtured by exams, to the truly awful beliefs that people do not like/are not able to learn certain subjects or skills – are firmly in the harmful category. It does mean that we need to be more aware of the hidden lessons, and of what our students are actually learning from them. We need to design our teaching in ways that allow them to make it relevant and meaningful in their lives. We need to design it so that every student can apply their learning to things that matter to them, we need to help them to reflect and connect, to adopt approaches, attitudes, and values that they can constantly use throughout their lives, in the workplace or not. We need to help them to see what they have learned in a broader social context, to pay it forward and spread their learning contagiously, both in and out of the classroom (or wherever they are doing their learning). We need to be partners and collaborators in learning, not providers. If we do that then, even if we are teaching COBOL, Italian Renaissance poetry, or some other ‘useless’ subject, we will be doing what employers seem to want and need. More importantly, we will be enriching lives, whether or not we make people fiscally richer.