I gave my second keynote of the week last week (in person!) at the excellent ICEEL conference in Tokyo. Here are the slides: Generative AI vs degenerative AI: steps towards the constructive transformation of education in the digital age. The conference theme was “AI-Powered Learning: Transforming Education in the Digital Age”, so this is roughly what I talked about…

I gave my second keynote of the week last week (in person!) at the excellent ICEEL conference in Tokyo. Here are the slides: Generative AI vs degenerative AI: steps towards the constructive transformation of education in the digital age. The conference theme was “AI-Powered Learning: Transforming Education in the Digital Age”, so this is roughly what I talked about…

Transformation in (especially higher) education is quite difficult to achieve. There is gradual evolution, for sure, and the occasional innovation, but the basic themes, motifs, and patterns – the stuff universities do and the ways they do it – have barely changed in nigh-on a millennium. A mediaeval professor or student would likely feel right at home in most modern institutions, now and then right down to the clothing. There are lots of path dependencies that have led to this, but a big part of the reason is down to the multiple subsystems that have evolved within education, and the vast number of supersystems in which education participates. Anything new has to thrive in an ecosystem along with countless other parts that have co-evolved together over the last thousand years. There aren’t a lot of new niches, the incumbents are very well established, and they are very deeply enmeshed.

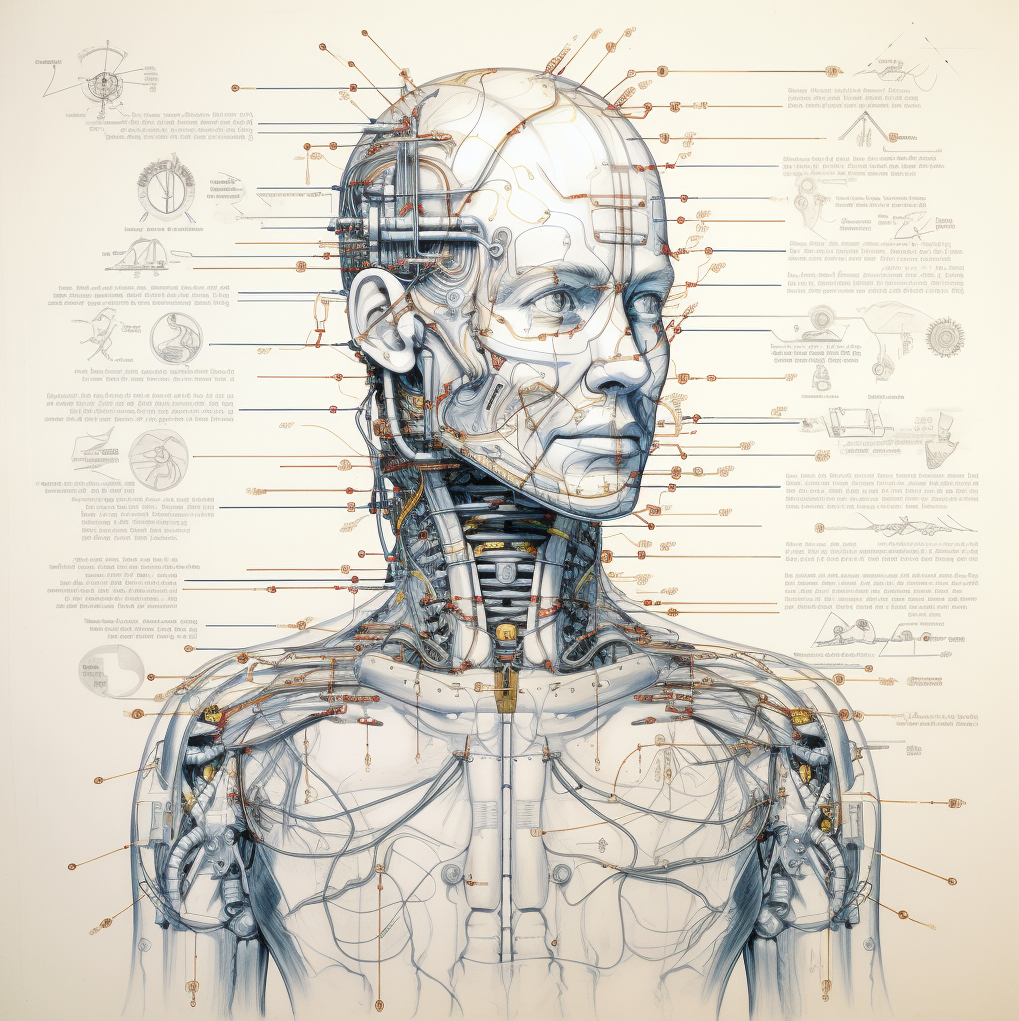

There are several reasons that things may be different now that generative AI has joined the mix. Firstly, generative AIs are genuinely different – not tools but cognitive Santa Claus machines, a bit like appliances, a bit like partners, capable of becoming but not really the same as anything else we’ve ever created. Let’s call them metatools, manifestations of our collective intelligence and generators of it. One consequence of this is that they are really good at doing what humans can do, including teaching, and students are turning to them in droves because they already teach the explicit stuff (the measurable skills and knowledge we tend to assess, as opposed to the values, attitudes, motivational and socially connected stuff that we rarely even notice) better than most human teachers. Secondly, genAI has been highly disruptive to traditional assessment approaches: change (not necessarily positive change) must happen. Thirdly, our cognition itself is changed by this new kind of technology for better or worse, creating a hybrid intelligence we are only beginning to understand but that cannot be ignored for long without rendering education irrelevant. Finally genAI really is changing everything everywhere all at once: everyone needs to adapt to it, across the globe and at every scale, ecosystem-wide.

There are huge risks that it can (and plentiful evidence that it already does) reinforce the worst of the worst of education by simply replacing what we already do with something that hardens it further, that does the bad things more efficiently, and more pervasively, that revives obscene forms of assessment and archaic teaching practices, but without any of the saving graces and intricacies that make educational systems work despite their apparent dysfunctionality. This is the most likely outcome, sadly. If we follow this path, it ends in model collapse for not just LLMs but for human cognition. However, just perhaps, how we respond to it could change the way we teach in good if not excellent ways. It can do so as long as human teachers are able to focus on the tacit, the relational, the social, and the immeasurable aspects of what education does rather than the objectives-led, credential-driven, instrumentalist stuff that currently drives it and that genAI can replace very efficiently, reliably, and economically. In the past, the tacit came for free when we did the explicit thing because the explicit thing could not easily be achieved without it. When humans teach, no matter how terribly, they teach ways of being human. Now, if we want it to happen (and of course we do, because education is ultimately more about learning to be than learning to do), we need to pay considerably more deliberate attention to it.

The table below, copied from the slides, summarizes some of the ways we might productively divide the teaching role between humans and AIs:

|

Human Role (e.g.) |

AI role (e.g.) |

|

|

Relationships |

Interacting, role modelling, expressing, reacting. | Nurturing human relationships, discussion catalyzing/summarizing |

|

Values |

Establishing values through actions, discussion, and policy. | Staying out of this as much as possible! |

|

Information |

Helping learners to see the personal relevance, meaning, and value of what they are learning. Caring. | Helping learners to acquire the information. Providing the information. |

|

Feedback |

Discussing and planning, making salient, challenging. Caring. | Analyzing objective strengths and weaknesses, helping with subgoals, offering support, explaining. |

|

Credentialling |

Responsibility, qualitative evaluation. | Tracking progress, identifying unprespecified outcomes, discussion with human teachers. |

|

Organizing |

Goal setting, reacting, responding. | Scheduling, adaptive delivery, supporting, reminding. |

|

Ways of being |

Modelling, responding, interacting, reflecting. | Staying out of this as much as possible! |

I don’t think this is a particularly tall order but it does demand a major shift in culture, process, design, and attitude. Achieving that from scratch would be simple. Making it happen within existing institutions without breaking them is going to be hard, and the transition is going to be complex and painful. Failing to do so, though, doesn’t bear thinking of.

Abstract

In all of its nearly 1000-year history, university education has never truly been transformed. Rather, the institution has gradually evolved in incremental steps, each step building on but almost never eliminating the last. As a result, a mediaeval professor dropped into a modern university would still find plenty that was familiar, including courses, semesters, assessments, methods of teaching and perhaps, once or twice a year, scholars dressed like him. Even such hugely disruptive innovations as the printing press or the Internet have not transformed so much as reinforced and amplified what institutions have always done. What chance, then, does generative AI have of achieving transformation, and what would such transformation look like?

In this keynote I will discuss some of the ways that, perhaps, it really is different this time: for instance, that generative AIs are the first technologies ever invented that can themselves invent new technologies; that the unprecedented rate and breadth of adoption is sufficient to disrupt stabilizing structures at every scale; that their disruption to credentialing roles may push the system past a tipping point; and that, as cognitive Santa Claus machines, they are bringing sweeping changes to our individual and collective cognition, whether we like it or not, that education cannot help but accommodate. However, complex path dependencies make it at least as likely that AI will reinforce the existing patterns of higher education as disrupt them. Already, a surge in regressive throwbacks like oral and written exams is leading us to double down on what ought to be transformed while rendering vestigial the creative, relational and tacit aspects of our institutions that never should. Together, we will explore ways to avoid this fate and to bring about constructive transformation at every layer, from the individual learner to the institution itself.