Late last night I gave the opening keynote at the Global AI Summit 2024, International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology, hosted by Bennett University, Noida, India. My talk was online. Here are the slides: How AI Teaches Its Children. It was recorded but I don’t know when or whether or with whom it will be shared: if possible I will add it to this post.

For those who have been following my thoughts on generative AI there will be few surprises in my slides, and I only had half an hour so there was not much time to go into the nuances. The title is an allusion to Pestalozzi’s 18th Century tract, How Gertrude Teaches Her Children, which has been phenomenally influential to the development of education systems around the world and that continues to have impact to this day. Much of it is actually great: Pestalozzi championed very child-centric teaching approaches that leveraged the skills and passions of their teachers. He recommended methods of teaching that made full use of the creativity and idiosyncratic knowledge the teachers possessed and that were very much concerned with helping children to develop their own interests, values and attitudes. However, some of the ideas – and those that have ultimately been more influential – were decidedly problematic, as is succinctly summarized in this passage on page 41:

I believe it is not possible for common popular instruction to advance a step, so long as formulas of instruction are not found which make the teacher, at least in the elementary stages of knowledge, merely the mechanical tool of a method, the result of which springs from the nature of the formulas and not from the skill of the man who uses it.

This is almost the exact opposite of the central argument of my book, How Education Works, that mechanical methods are not the most important part of a soft technology such as teaching: what usually matters more is how it is done, not just what is done. You can use good methods badly and bad methods well because you are a participant in the instantiation of a technology, responsible for the complete orchestration of the parts, not just a user of them.

As usual, in the talk I applied a bit of co-participation theory to explain why I am both enthralled by and fearful of the consequences of generative AIs because they are the first technologies we have ever built that can use other technologies in ways that resemble how we use them. Previous technologies only reproduced hard technique – the explicit methods we use that make us part of the technology. Generative AIs reproduce soft technique, assembling and organizing phenomena in endlessly novel ways to act as creators of the technology. They are active, not passive participants.

Two dangers

I see there to be two essential risks lying in the delegation of soft technique to AIs. The first is not too terrible: that, because we will increasingly delegate creative activities we would have otherwise performed ourselves to machines, we will not learn those skills ourselves. I mourn the potential passing of hard skills in (say) drawing, or writing, or making music, but the bigger risk is that we will lose the the soft skills that come from learning them: the things we do with the hard skills, the capacity to be creative.

That said, like most technologies, generative AIs are ratchets that let us do more than we could achieve alone. In the past week, for instance, I “wrote” an app that would have taken me many weeks without AI assistance in a less than a day. Though it followed a spec that I had carefully and creatively written, it replaced the soft skills that I would have applied had I written it myself, the little creative flourishes and rabbit holes of idea-following that are inevitable in any creation process. When we create we do so in conversation with the hard technologies available to us (including our own technique), using the affordances and constraints to grasp adjacent possibles they provide. Every word we utter or wheel we attach to an axle opens and closes opportunities for what we can do next.

With that in mind, the app that the system created was just the beginning. Having seen the adjacent possibles of the finished app, I have spent too many hours in subsequent days extending and refining the app to do things that, in the past, I would not have bothered to do because they would have been too difficult. It has become part of my own extended cognition, starting higher up the tree than I would have reached alone. This has also greatly improved my own coding skills because, inevitably, after many iterations, the AI and/or I started to introduce bugs, some of which have been quite subtle and intractable. I did try to get the AI to examine the whole code (now over 2000 lines of JavaScript) and rewrite it or at least to point out the flaws, but that failed abysmally, amply illustrating both the strength of LLMs as creative participants in technologies, and their limitations in being unable to do the same thing the same way twice. As a result, the AI and I have have had to act as partners trying to figure out what is wrong. Often, though the AI has come up with workable ideas, its own solution has been a little dumb, but I could build on it to solve the problem better. Though I have not actually created much of the code myself, I think my creative role might have been greater than it would have been had I written every line.

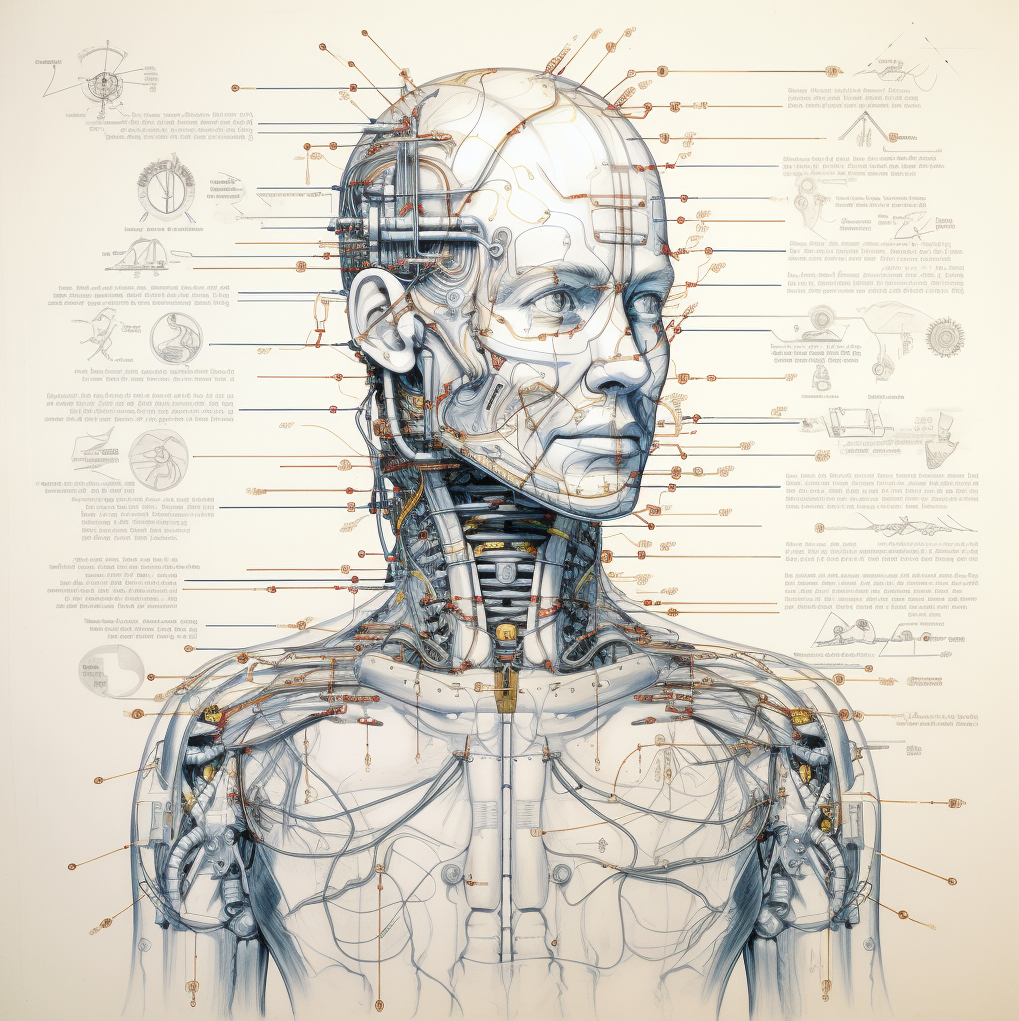

Similarly for the images I used to illustrate the talk: I could not possibly have drawn them alone but, once the AI had done so, I engaged in a creative conversation to try (sometimes very unsuccessfully) to get it to reproduce what I had in mind. Often, though, it did things that sparked new ideas so, again, it became a partner in creation, sharing in my cognition and sparking my own invention. It was very much not just a tool: it was a co-worker, with different and complementary skills, and “ideas” of its own. I think this is a good thing. Yes, perhaps it is a pity that those who follow us may not be able to draw with a pen (and more than a little worrying thinking about the training sets that future AIs with learn to draw from), but they will have new ways of being creative.

Like all learning, both these activities changed me: not just my skills, but my ways of thinking. That leads me to the bigger risk.

Learning our humanity from machines

The second risk is more troubling: that we will learn ways of being human from machines. This is because of the tacit curriculum that comes with every learning interaction. When we learn from others, whether they are actively teaching, writing textbooks, showing us, or chatting with us, we don’t just learn methods of doing things: we learn values, attitudes, ways of thinking, ways of understanding, and ways of being at the same time. So far we have only learned that kind of thing from humans (sometimes mediated through code) and it has come for free with all the other stuff, but now we are doing so from machines. Those machines are very much like us because 99% of what they are – their training sets – is what we have made, but they not the same. Though LLMs are embodiments of our own collective intelligence, they don’t so much lack values, attitudes, ways of thinking etc as they have any and all of them. Every implicit value and attitude of the people whose work constituted their training set is available to them, and they can become whatever we want them to be. Interacting with them is, in this sense, very much not like interacting with something created by a human, let alone with humans more directly. They have no identity, no relationships, no purposes, no passion, no life history and no future plans. Nothing matters to them.

To make matters worse, there is programmed and trained stuff on top of that, like their interminable cheery patience that might not teach us great ways of interacting with others. And of course it will impact how we interact with others because we will spend more and more time engaged with it, rather than with actual humans. The economic and practical benefits make this an absolute certainty. LLMs also use explicit coding to remove or massage data from the input or output, reflecting the values and cultures of their creators for better or worse. I was giving this talk in India to a predominantly Indian audience of AI researchers, every single one of whom was making extensive use of predominantly American LLMs like ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude, and (inevitably) learning ways of thinking and doing from it. This is way more powerful than Hollywood as an instrument of Americanization.

I am concerned about how this will change our cultures and our selves because this is happening at phenomenal and global scale, and it is doing so in a world that is unprepared for the consequences, the designed parts of which assume a very different context. One of generative AI’s greatest potential benefits lies in the potential to provide “high quality” education at low cost to those who are currently denied it, but those low costs will make it increasingly compelling for everyone. However, because of the designs that assume a different context “quality”, in this sense, relates to the achievement of explicit learning outcomes: this is Pestalozzi’s method writ large. Generative AIs are great at teaching what we want to learn – the stuff we could write down as learning objectives or intended outcomes – so, as that is the way we have designed our educational systems (and our general attitudes to learning new skills), of course we will use them for that purpose. However, that cannot be done without teaching the other stuff – the tacit curriculum – which is ultimately more important because it shapes how we are in the world, not just the skills we employ to be that way. We might not have designed our educational systems to do that, and we seldom if ever think about it when teaching ourselves or receiving training to do something, but it is perhaps education’s most important role.

By way of illustration, I find it hugely bothersome that generative AIs are being used to write children’s stories (and, increasingly, videos) and I hope you feel some unease too, because those stories – not the facts in them but the lessons about things that matter that they teach – are intrinsic to them becoming who they will become. However, though perhaps of less magnitude, the same issue relates to learning everything from how to change a plug to how to philosophize: we don’t stop learning from the underlying stories behind those just because we have grown up. I fear that educators, formal or otherwise, will become victims of the McNamara Fallacy, setting our goals to achieve what is easily measurable while ignoring what cannot (easily) be measured, and so rush blindly towards subtly new ways of thinking and acting that few will even notice, until the changes are so widespread they cannot be reversed. Whether better or worse, it will very definitely be different, so it really matters that we examine and understand where this is all leading. This is the time, I believe, to reclaim a revalorize the value of things that are human before it is too late. This is the time to recognize education (far from only formal) as being how we become who we are, individually and collectively, not just how we meet planned learning outcomes. And I think (at least hope) that we will do that. We will, I hope, value more than ever the fact that something – be it a lesson plan or a book or a screwdriver – is made by someone or by a machine that has been explicitly programmed by someone. We will, I hope, better recognize the relationships between us that it embodies, the ways it teaches us things it does not mean to teach, and the meaning it has in our lives as a result. This might happen by itself – already there is a backlash against the bland output of countless bots – but it might not be a bad idea to help it along when we can. This post (and my talk last night) has been one such small nudge.